By the end of this page, you'll stop wondering what's wrong with you — why you're falling apart while he's recovering fine. And the nightmares that feel like you're losing your mind? They'll start to feel like exactly what they are: your brain finishing what it started at 3:30 AM.

It starts the same way every time — you were the capable one.

You used to be the strong one.

First in your family to go to university. High-flying career. The person everyone counted on to hold things together when life got hard.

And now you can't walk into your own living room without feeling sick. You're on sick leave. You can't work. The nightmares won't stop. Memories you thought you'd buried years ago are forcing their way back.

Meanwhile, your husband—the one who actually had the heart attack—is recovering brilliantly. He's doing fine. And you're falling apart.

If you're anything like most people in this situation, there's a voice in your head saying: What is wrong with me? This happened to him, not me. I should be stronger than this.

That voice is wrong. And understanding why it's wrong will change everything.

What Nobody Tells You About Who Really Experiences Trauma

Let me pose a scenario.

A soldier watches their closest friend nearly die in combat. They have to keep their friend alive until help arrives. They don't know if help will come in time. Every decision they make could mean life or death.

Months later, that soldier can't go near the place where it happened without feeling physically ill. Loud noises make them duck. Nightmares replay the event over and over.

Would you tell that soldier they should be "stronger than this"? That it happened to their friend, not to them, so they shouldn't be affected?

Of course not. We recognize that as trauma.

Now here's what I want you to consider: At 3:30 in the morning, alone, watching someone you love collapse—not knowing if they would live or die—calling emergency services while trying to keep them conscious—

What, exactly, is the difference?

Why Your Brain Can't Tell the Difference Between Their Danger and Yours

Here's something that surprises most people: research shows that witnessing a loved one's potential death registers in your brain the same way as facing your own death.

Your brain doesn't have separate categories for "danger to me" and "danger to person I love." When you watched your husband collapse, your threat detection system fired at full capacity. It recorded every detail of those moments with the same intensity it would have if you were the one dying.

Key Insight

This isn't weakness. This isn't failure. This is how human brains are designed to work.

Studies on partners of cardiac patients have found that the person who witnesses the cardiac event often develops more severe post-traumatic symptoms than the patient themselves. One piece of research published in Frontiers in Psychology specifically identified "Cardiac-Disease-Induced PTSD" in partners—a pattern so common it has its own clinical name.

The criteria for PTSD in the DSM-5—the diagnostic manual used by mental health professionals worldwide—explicitly includes "witnessing, in person, the event as it occurred to others." Witnessing your spouse's potential death qualifies.

You didn't avoid trauma because it "happened to him." You experienced trauma because you were there.

The Truth About What Happens When You 'Pack Away' Your Grief

But here's where it gets more complicated.

Your mother died in 2015. You were with her. She died in your arms after a rapid decline from a rare illness.

And afterward? You "packed it away." There was too much to do. You had to be strong for everyone else. You got on with things.

Imagine a bottle of fizzy drink. Every time something difficult happens, instead of opening it a little to let the pressure out, you shake it and shove it in a cupboard. What happens to that bottle over time?

The pressure builds. And eventually, when something forces the cupboard open—

It explodes.

Your husband's heart attack didn't just give you new trauma. It opened the cupboard. What's flooding out now isn't just from eight weeks ago. It's everything you suppressed to stay strong. The grief for your mother. The fear. The helplessness. Seven years of pressure, finally finding an exit.

Research on grief and trauma shows this pattern repeatedly: unprocessed traumatic loss doesn't go away—it waits. Studies demonstrate that PTSD can actually block the natural grief process, creating what researchers call a "complex synergy" between trauma and grief. The emotions don't dissolve; they compound.

You didn't fail to process your mother's death. You did what you had to do to survive that period. But suppressing emotions has a cost, and the bill eventually comes due.

Why Your Nightmares Don't Mean You're Broken

Here's the part that terrifies most people.

The intrusive memories. The nightmares. The way your brain keeps pulling you back to that night, replaying it over and over without your permission.

It feels like losing your mind. Like something is broken beyond repair.

But what if these symptoms aren't signs of breakdown? What if they're signs of something else entirely?

Think about what happens after you work out muscles you haven't used in years. The next day, you're sore. Everything aches. If you didn't understand exercise, you might think something was terribly wrong.

But that soreness isn't damage—it's repair. It's your body rebuilding stronger.

The intrusive memories work the same way.

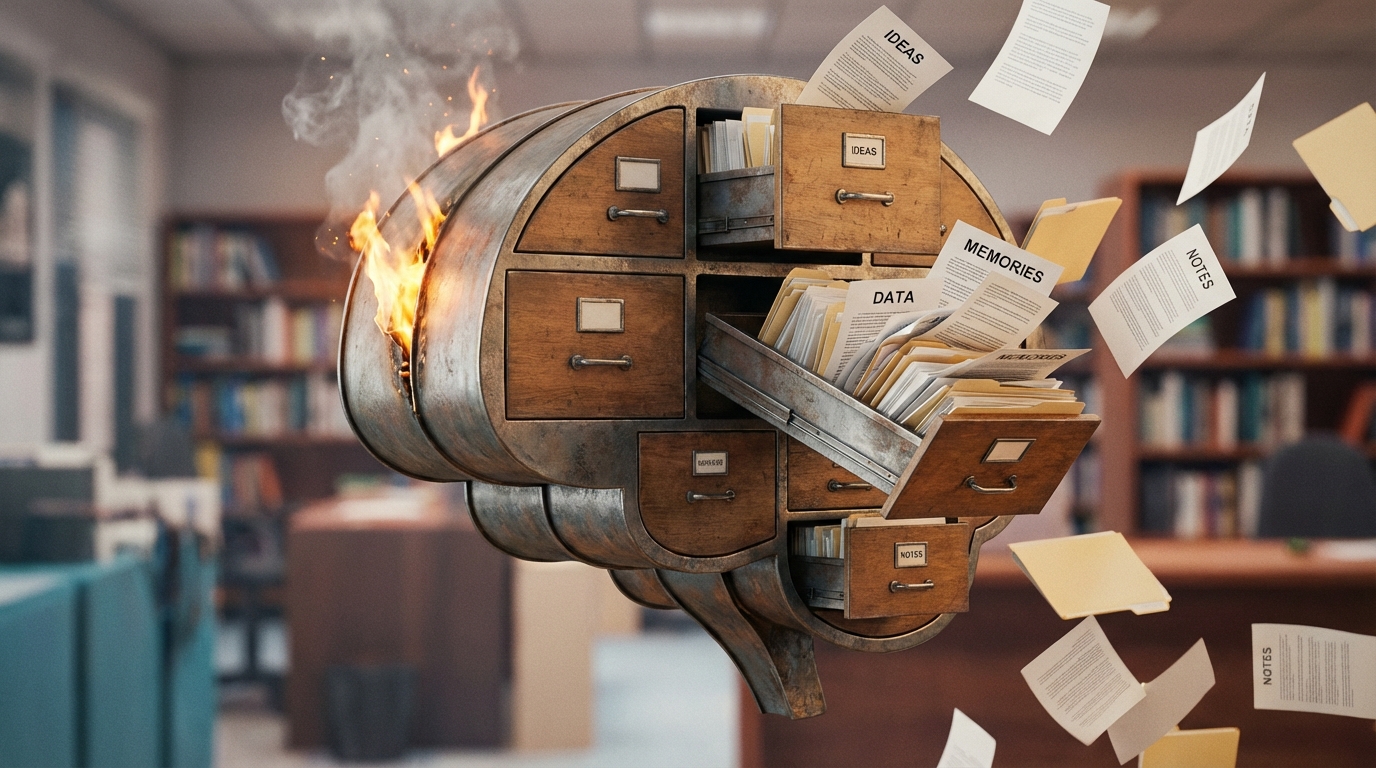

Your brain has a filing system for memories. Normal memories get processed, integrated, and stored away as "past events." They become stories you can tell without reliving them.

But traumatic memories don't get filed properly. They're too overwhelming to process in the moment, so they get stored in a raw, unprocessed form. And your brain knows they don't belong there.

So it keeps bringing them back up. Not to torture you—to try again at processing them. Every nightmare, every intrusion, is your brain's attempt to finally file these memories where they belong.

Important Clinical Note: Research on intrusive memories confirms this: in the weeks and months following trauma, these experiences are common and represent normal processing. They're not pathology. They're your brain doing exactly what it's designed to do with unintegrated threat.

The intrusions aren't evidence that you're losing your mind. They're evidence that your mind is trying to heal.

What Happens When Trauma Rewrites Your Beliefs About Safety

There's one more piece to understand.

Remember the soldier who ducks at loud noises? Their brain learned that loud noises mean danger. Even safe sounds—a car backfiring, a door slamming—trigger the same response. Because their brain changed its rules about what's safe.

Trauma doesn't just create bad memories. It rewrites your core beliefs.

Before that night, you believed your living room was safe. You believed you were mentally strong and capable. You believed your home was a place of comfort.

After that night? Your brain updated its files:

- The living room: DANGER ZONE

- This house: WHERE PEOPLE ALMOST DIE

- My identity: PERSON WHO COULDN'T COPE

Researchers call this "schema change"—the way trauma fundamentally alters beliefs about self, world, and safety. When people with trauma report thoughts like "I don't know myself anymore" or "I've permanently changed for the worse," they're describing this phenomenon.

You haven't become weak. Your beliefs about yourself got rewritten by an experience that overwhelmed your processing capacity. The person you were is still there—but you're looking at yourself through a lens that got smashed and reassembled wrong.

This is a recognized feature of PTSD. Studies on identity disruption show it's associated with more severe symptoms and lower life satisfaction—but also that it can be addressed. The lens can be corrected.

What All This Means for You

Let's put these pieces together.

You experienced legitimate trauma by witnessing your husband's cardiac event. Your brain registered it as a life-threatening experience because, functionally, that's exactly what it was.

The intrusive symptoms you're experiencing—nightmares, flashbacks, the memories forcing their way in—aren't signs that you're broken. They're your brain's normal attempts to process and integrate what happened. It's not malfunction. It's function.

The intensity of your reaction makes sense because you're not just processing one trauma. The cupboard is open, and years of suppressed grief are demanding attention alongside the recent terror.

And your shattered sense of self—the feeling that you're not the capable, strong person you used to be—isn't evidence of failure. It's evidence of schema change, a recognized phenomenon where trauma rewrites core beliefs. Your identity wasn't weak; it was updated by an experience that exceeded your processing capacity.

None of this means you're losing your mind. All of it means your mind is doing exactly what minds do with overwhelming threat.

How to Use This Understanding to Start Healing

Understanding what's happening won't instantly resolve it—but it transforms your relationship with the symptoms.

First: Review this model daily. Sketch the fizzy drink bottle. Draw the soldier ducking at loud noises. When the intrusive memories come, remind yourself: My brain is trying to process this. This is normal. This is what brains do with trauma.

The goal isn't to stop the thoughts. It's to change what the thoughts mean. "I'm going crazy" becomes "I'm healing."

Second: Share this with your husband. You've been trying to protect him from how bad it is. But keeping it secret isolates you, and isolation maintains PTSD. He doesn't need protection—he needs to understand what's happening in your brain so he can actually support you.

You don't have to carry this alone. You're not supposed to.

Third: Expect the emotional rawness—and reframe it. When the feelings hit hard, that's not evidence you're getting worse. That's evidence your brain is finally processing what you suppressed to survive. The soreness after exercise hurts, but it means the workout is working.

Clinical guidelines for PTSD treatment identify psychoeducation—understanding what's happening—as a core component of recovery. This isn't just information. It's the foundation that makes everything else possible.

Why Knowing the Truth Isn't Enough (And What Comes Next)

Here's what you now understand: why your brain is doing this. The alarm system. The processing attempts. The schema changes. The suppressed grief finally finding its exit.

But understanding alone raises a new question.

If your brain has updated its beliefs—if your living room now registers as "danger zone" even though you know your husband survived—why doesn't knowing that change how you feel?

Your brain has separated the knowing from the feeling. You can know, logically, that the danger has passed. But your alarm system hasn't received that update. It's still treating that room, that time of night, that memory, as present threats rather than past events.

There's a reason why trauma gets stuck in "present danger" mode. And there's a process for helping your brain finally file these memories away as past—so you can remember what happened without reliving it.

That's where the real work happens: reconnecting what you know with what you feel.

But first, you needed to understand what you're working with. Now you do.

Key Takeaway

Your brain isn't broken. It's doing exactly what it was designed to do. The question now is how to help it finish the job.

Comments

Leave a Comment