She offered support when your mother was rushed to hospital. For a moment—just a moment—you felt something shift. Maybe she finally sees you as a person, not just a resource to manage. Maybe things will be different now.

Then she threatened to dock your pay for the same hospital visit.

And here's the part that haunts you: some part of you will fall for it again. The next time she shows an ounce of warmth, hope will rise unbidden. After everything—after years of this—you'll catch yourself thinking maybe this time it's real.

What's wrong with you?

Nothing. Your brain is doing exactly what it's designed to do.

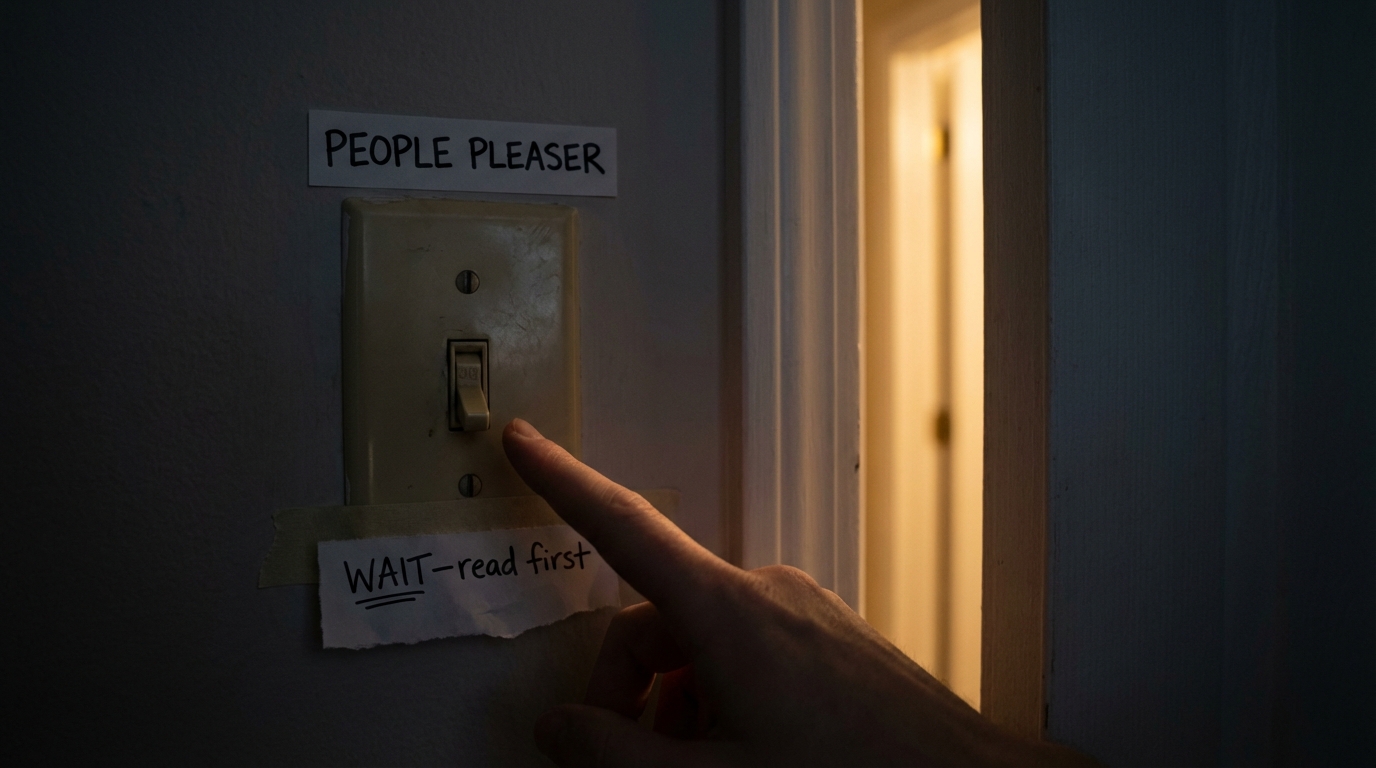

The Slot Machine in Your Office

Let me ask you a question that might seem unrelated.

If a slot machine paid out every single time you pulled the lever, how long would you play it? Not long. You'd take your winnings and leave—no excitement, no mystery.

Now imagine a slot machine that never paid out. Not once. How long would you play that one?

You'd give up almost immediately. Why bother?

So which slot machine keeps people sitting for hours, feeding in money they can't afford to lose?

The one that pays out sometimes. Unpredictably. Occasionally.

Your manager operates on the same principle.

The Truth About Why You Can't Let Go

What you can't see—what nobody tells you about inconsistent kindness—is that there's a mechanism running behind the scenes. Psychologists call it intermittent reinforcement.

When kindness comes unpredictably, your brain responds differently than it does to consistent kindness. The unpredictability creates a behavioral pattern that's extremely difficult to break. Research on this phenomenon shows that intermittent expressions of care become more sought after precisely because they can't be predicted. The inability to anticipate when warmth will appear makes each instance more valuable.

This is the same neurological pathway that drives gambling addiction. The same brain chemistry. The same hook.

Your manager isn't just difficult. She's neurologically addictive.

Why Knowing Better Doesn't Stop the Hope

Here's what makes this so frustrating: understanding that she won't change doesn't stop the hope. You can recite her pattern from memory. You could probably predict her next move. And yet—when she's nice, something in you responds.

That's not weakness. That's not naivety. That's your brain responding to a variable reinforcement schedule exactly the way human brains are wired to respond.

If you were naive, you would have given up after the first few disappointments. The fact that hope persists despite overwhelming evidence is precisely what this mechanism produces. You're not broken. You're caught in a well-documented psychological trap.

What Changes When You Name the Trap

Once you see the mechanism, you can name it.

The next time she shows unexpected warmth and hope flickers in your chest, you can say: This is intermittent reinforcement. My brain is responding to unpredictability, not reality.

You can't stop the feeling. But you can stop believing it.

The hope isn't a message that things are changing. It's a neurological reflex. Treat it like one.

Is Your Documentation Obsession or Self-Defense?

There's something else that might be weighing on you—something you may not have told many people about.

Maybe you've been documenting. Every incident, every shifted story, every promise made and broken. Perhaps you have pages of records. Perhaps someone has suggested this is obsessive.

But here's what I want you to consider: Why did you start documenting in the first place?

Most people who create these records started because they began doubting their own memory. She said something, then denied it happened. He changed the story. You started wondering if you were imagining things.

The documentation wasn't about her. It was about protecting your own perception of reality.

Research on workplace gaslighting confirms this: keeping detailed records serves a critical psychological function. It validates your experience when someone is working to make you doubt it. Documentation combats confusion tactics. It's not rumination—it's mental self-defense.

The real question isn't "why do you have so many pages of documentation?"

The real question is: what kind of environment requires someone to keep written proof just to trust their own experience?

What Nobody Tells You About Passive-Aggressive Retaliation

There's one more thing that might be eating at you. Something you're probably not proud of.

Maybe you've dragged your feet on deadlines. Done the minimum when you could have done more. Found small ways to frustrate her that couldn't be pinned on you directly. You know it's petty. You know it makes things worse.

But consider this: what happens when you try to address problems directly?

She denies them. Turns things around. Demands information you shouldn't have to give. Direct confrontation feels unsafe—because it is unsafe.

So what options do you have left?

Passive-aggressive behavior is what happens when assertiveness gets suppressed long enough. It's not a character defect. It's a predictable result of having no safe outlet.

Here's the counterintuitive part: if you value diplomacy and kindness—if you're someone who naturally tries to be reasonable—you're actually more likely to develop passive-aggressive patterns. Because the frustration doesn't disappear when you suppress it. It finds another exit.

The same quality that makes you diplomatic creates pressure when suppression becomes constant. Your frustration leaked out through the only door you left open.

Understanding this doesn't excuse it. But it does explain it. And explanation is the first step toward choosing differently.

How to Stop Self-Criticism Without Trying

Here's a technique that research shows actually works.

Imagine someone you care about came to you with your exact situation. They work nights on a side project while managing therapy during the day. Their mother's health is declining rapidly. Their manager offered support for a hospital visit then threatened to dock their pay. They've been documenting incidents for years. They sometimes resist in small ways because direct communication feels dangerous.

What would you tell them?

My guess: you'd tell them they're dealing with an impossible amount of pressure. That their reactions make complete sense. That they're not the problem—they're surviving.

Studies on what psychologists call "self-distancing" show something remarkable: people display wiser reasoning about others' problems than their own. We're harsher critics of ourselves than we would ever be of friends facing the same circumstances.

But here's the key finding: imagining you're advising a friend eliminates this asymmetry. You become as wise about your own situation as you would be about theirs.

When you catch yourself in self-criticism, ask: What would I tell someone I love who was facing exactly this?

Then listen to your own answer.

The Vigilance Mistake That Bleeds Into Safe Relationships

One more thing worth noting.

The vigilance you've developed—the documentation, the pattern-recognition, the wariness—makes complete sense for someone whose reality is regularly denied. But that vigilance can bleed into places where it doesn't belong.

Your wife isn't your manager. Not everyone is trying to deceive you.

Some contexts require self-protection. Others deserve the assumption of good faith. The skill isn't being vigilant everywhere or trusting everywhere. It's matching your response to the actual situation.

The same approach doesn't fit every relationship. And recognizing that difference—applying protection where it's needed and trust where it's deserved—is a sign of clarity, not confusion.

5 Actions to Take Right Now

Keep documenting. It's not obsession. It's evidence. It's your anchor to reality when someone is trying to make you doubt it.

Name the mechanism. When hope rises after unexpected kindness, say it out loud or in your head: "This is intermittent reinforcement. My brain is responding to unpredictability, not to change." You can't stop the feeling, but you can stop treating it as information.

Use the friend test. When self-criticism hits, imagine advising someone you love through the same situation. Trust the wisdom that emerges.

Channel, don't display. The frustration is real. But passive resistance creates ammunition against you. Can you channel that energy into your documentation instead? Into building your exit? You mentioned building software that people actually buy. That's not a side project. That's a door.

Protect your other relationships. Match your response to the context. Vigilance where it's warranted. Trust where it's deserved.

The Real Question That Matters Now

The pattern won't change while you're there. What you can control is how much real estate it occupies in your mind—and what you're building while you wait.

You're not addicted to her. You're caught in a neurological trap that anyone would get caught in. Knowing this doesn't make the trap disappear. But it does let you stop blaming yourself for being in it.

And that frees up energy for the only question that actually matters now: What are you building on your way out?

There's a deeper question lurking beneath all of this: if intermittent reinforcement creates the trap, how do you actually protect your mental boundaries with someone who has power over you—especially when direct confrontation makes things worse? That's worth exploring next.

What's Next

How do you actually build boundaries with someone who has power over you—protecting yourself without creating ammunition against yourself?

Comments

Leave a Comment