She offered support when your mother got sick. A week later, she threatened to dock your pay for visiting the hospital.

He praised your work in Monday's meeting. By Thursday, he was suggesting you piggyback off colleagues' efforts.

They set a deadline. Then changed it. Then blamed you for missing the version they never told you about.

And somehow, despite everything, you keep hoping. Every time they're kind, something in you whispers: Maybe it's different now. Maybe they've changed.

Then the cruelty returns, and you feel foolish all over again.

If you've been caught in this cycle, you've probably wondered what's wrong with you. Why do you keep getting sucked back in? Why can't you just stop caring what they think?

Here's the uncomfortable truth: there's nothing wrong with you. But there's something happening to you that you can't see—a psychological mechanism that's been studied extensively, and it explains everything.

The Cycle You're Stuck In (And Can't See)

Let's map what you're actually experiencing.

Your manager (or colleague, or supervisor) is inconsistent. Sometimes they're supportive, even warm. Other times, they're dismissive, threatening, or outright cruel. You never know which version you're going to get.

Between interactions, you find yourself replaying conversations. Did that really happen? You leave meetings feeling foggy, uncertain. Your memory—normally sharp—seems to fail you specifically around this person.

Maybe you've started documenting things. Writing down what was said, when it was said, what happened next. You might have pages of notes by now. And part of you wonders: Is this obsessive? Am I the problem here?

You've also noticed something else. Sometimes you don't do what they ask. Not openly—you're not that direct. You just... don't do it. Or you do it wrong. It feels satisfying in the moment, then pathetic afterward.

And underneath it all, you keep hoping. Every nice moment makes you think: This time.

Every cruel moment devastates you—even though you should know better by now.

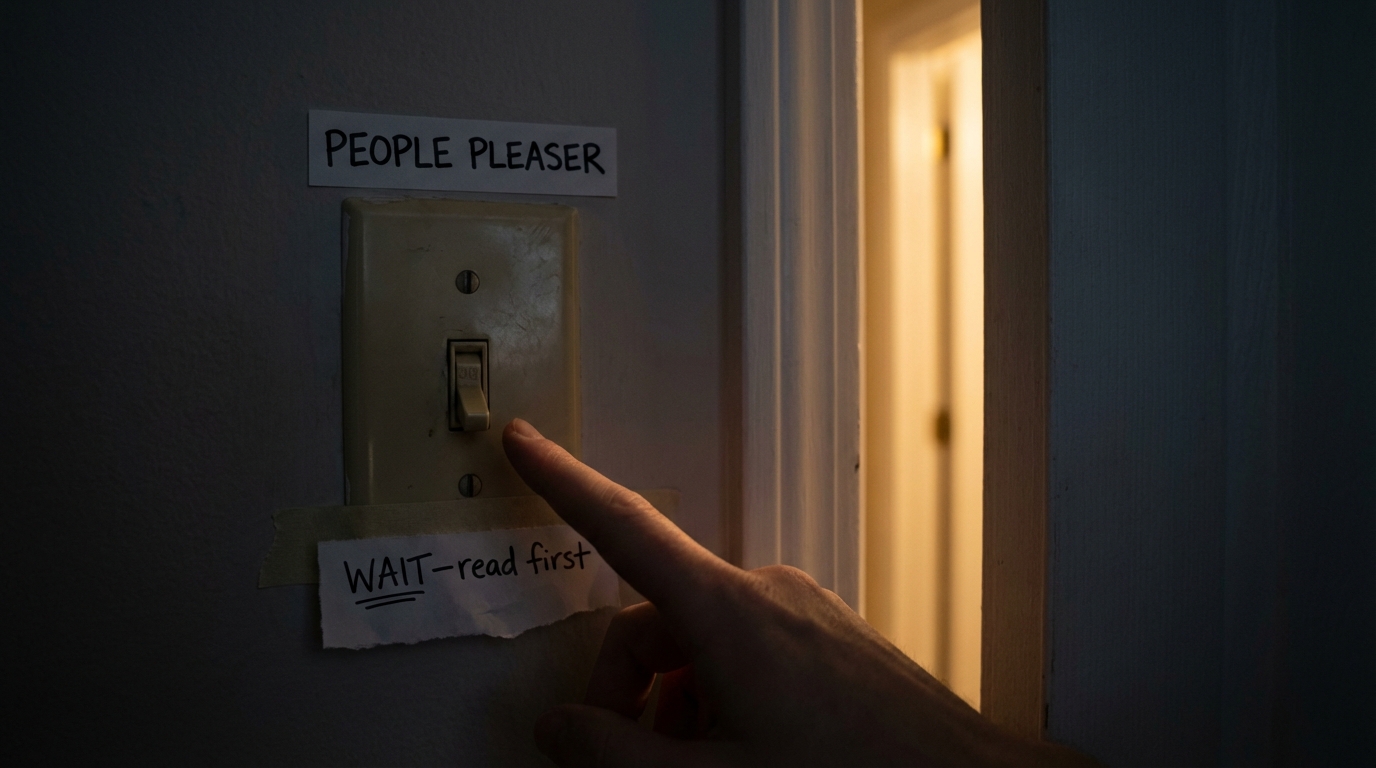

Why Your Brain Keeps Pulling the Lever

Here's what most people never see about situations like this.

Imagine a vending machine. You put in a dollar, you get a snack. Reliable. Predictable. Now imagine that same machine only works sometimes—randomly, unpredictably. Sometimes your dollar gives you nothing. Sometimes it gives you three snacks.

Which machine would you walk away from faster if it stopped working?

The reliable one. Obviously.

The unpredictable one keeps you feeding in dollars, hoping this is the time it pays out.

This is called intermittent reinforcement, and research shows it creates attachment bonds that are remarkably difficult to break. Studies have found that unpredictable reward schedules—kindness mixed randomly with cruelty—increase the likelihood of staying in harmful relationships by more than three times compared to consistent treatment.

Your manager isn't complicated. They're a slot machine.

The nice moments are random jackpots. And your brain is wired to keep pulling the lever, hoping this time—this time—the nice version will stay.

This isn't weakness. It's not stupidity. It's not a character flaw.

It's how human psychology works when exposed to unpredictable rewards. The same mechanism that makes gambling addictive is operating in your workplace. You didn't sign up for it, but you're caught in it.

Why Your Memory Fails Only With This One Person

Here's something interesting.

If I asked you to recall a complex logic chain from last week's coding session, you'd probably do fine. If you had to remember the details of a conversation with a friend, no problem.

But with this person, everything gets foggy.

That's not a coincidence.

When someone tells you one thing, then later denies saying it—when they minimize what happened, when they change stories, when their behavior is wildly inconsistent—your brain struggles to create a stable memory. Research on workplace psychological manipulation has documented specific tactics: denial, deception, dismissal, minimization, behavioral inconsistency.

The term for this is gaslighting, and its purpose is exactly what you're experiencing: to make you doubt your own perception of reality.

The confusion you feel isn't evidence that something's wrong with your memory.

It's evidence that something is being done to your perception.

Your 34 Pages Aren't Obsession—They're Self-Preservation

Those pages of notes you've accumulated? The dates, the quotes, the incidents you've written down over months or years?

You probably wonder if that's obsessive. If keeping such detailed records means you're the one with the problem.

Consider this: before this person, did you typically need to write down conversations to remember them accurately?

Probably not.

You started documenting because you couldn't trust your own memory—specifically with this one person. You were trying to create something external that would stay stable when your internal certainty kept getting scrambled.

Psychological research validates documentation as a recommended strategy for maintaining your grip on reality in gaslighting situations. It's not paranoia. It's not rumination. It's building a reality anchor—something you can return to when they try to rewrite what happened.

Your 34 pages (or however many you have) aren't evidence of obsession.

They're evidence of self-preservation.

The Passive-Aggressive Response You're Ashamed Of (And Shouldn't Be)

Now let's talk about the passive-aggressive stuff. The times you deliberately don't do what they expect. The subtle resistance that feels satisfying, then shameful.

Ask yourself: what are your options for pushing back directly?

If you confronted them openly, what would happen? Based on what you know about this person—their pattern of twisting words, denying conversations, potentially escalating—would direct confrontation be safe?

For most people in these situations, the honest answer is no.

So what happens to the natural human need to resist unfair treatment when there's no safe outlet for it?

It comes out sideways.

Clinical research shows that passive-aggressive behavior naturally emerges when assertiveness is suppressed, particularly in relationships with a power imbalance. It's not a character flaw you should be ashamed of. It's a predictable consequence of having no safe way to assert yourself directly.

You're not petty. You're not pathetic.

You're human, operating in a system that's blocked all your healthy outlets.

Understanding this doesn't mean passive-aggression is a good long-term strategy. It's a symptom, not a solution. But removing the shame from it is the first step toward choosing different responses consciously.

What Would You Tell a Friend in Your Situation?

Try something.

Imagine a friend came to you with your exact situation. Same manager patterns. Same documentation. Same cycles of hope and disappointment. Same passive-aggressive responses.

What would you tell them?

Most people, when they actually do this exercise, find themselves saying things like:

You're being mistreated at work. Your documentation is smart. You're not crazy. The passive-aggressive stuff makes sense even if it's not ideal. You're surviving a difficult situation.

They'd be kind to their friend.

Now compare that to what you tell yourself. Petty. Pathetic. Obsessive. Weak. Foolish for hoping.

Why the double standard?

This technique—imagining yourself advising a friend in your situation—is backed by research on self-distancing. It creates psychological distance that reduces self-criticism by revealing the gap between how we treat others and how we treat ourselves.

You deserve the same compassion you'd offer a friend.

Once You See It, Everything Shifts

Once you understand the mechanics of what's happening, several things shift.

The hope makes sense. You're not foolish for hoping they'll change. Your brain is responding to intermittent reinforcement the same way every human brain does. You can't eliminate the hope, but you can label it: "This is the slot machine paying out. The pattern is still the pattern." That creates distance without requiring you to suppress what you feel.

The documentation makes sense. You're not obsessive. You're protecting your grip on reality against someone who's trying to destabilize it. Keep documenting—but now without the shame attached.

The passive-aggression makes sense. It's blocked assertiveness finding an outlet. When you catch yourself in it, instead of shame, try asking: "What am I actually wanting to assert here?" You might not be able to assert it directly with them. But naming the need reduces the pressure that comes out sideways.

The confusion makes sense. It's not your memory failing. It's a predictable response to unpredictable behavior and deliberate reality-distortion.

You're not weak. You're not broken. You're not the problem.

You're a human being caught in a well-documented psychological trap, responding exactly as humans do.

4 Shifts You Can Make Today

Four practical shifts you can make immediately:

1. Reframe your documentation. Next time you add to your notes, remind yourself: this is a reality anchor, not rumination. The instinct to document was healthy self-preservation from the start.

2. Label the slot machine moments. When they're nice and you feel hope rising, don't fight the feeling—just narrate it internally: "This is the slot machine paying out. I notice I feel hopeful. The pattern is still the pattern." This creates analytical distance from the emotional pull.

3. Ask what you're trying to assert. When you catch passive-aggressive impulses, pause and ask: "What am I actually wanting to say or do here?" The act of naming it reduces the pressure—even if you can't express it directly.

4. Use the friend technique for self-criticism. When you start calling yourself pathetic or obsessive or weak, stop and ask: "What would I tell a friend in this situation?" Let that cut through the self-attack.

What Comes Next

There's something we haven't touched on that might be worth exploring.

You mentioned (or perhaps noticed) that this person pushes for information they have no right to—demanding to know your bonus amount, who your coach is, other confidential details.

That boundary-pushing behavior serves a specific function in manipulation dynamics. It's not random. There's a reason certain people insist on access to information that isn't theirs to have.

Understanding what that function is—and why it matters—might change how you respond to those demands.

But that's the next layer to uncover.

For now, sit with this: the patterns you've been living through have names. The responses you've been shaming yourself for are predictable, documented, and—in their own way—evidence that you've been trying to protect yourself all along.

You weren't the problem.

You were just too close to see the trap.

What's Next

Why does the manager demand confidential information (bonus amount, coach's name), and what function does this boundary-pushing serve in manipulation dynamics?

Comments

Leave a Comment